Posts Tagged curriculum

Mastery, risk-taking and play

Posted by kmcg2375 in education, learning community, research, video games on November 29, 2011

This post is a culmination of a week or so of talking about play-based education. If that’s its official term for it? I don’t know. I must declare my rookie status in this field, which means you should feel really free to jump into the comment s section below and school me on what I’ve missed!

Thanks to @malynmawby, @vormamim, @biancah80, and @benpaddlejones for their ideas via twitter and email. You can read more about @malynmawby ‘s experiences with play-based learning here, here and here.

Play-based Learning: Another PBL?

My current interest in project-based learning has also put me in contact with the terms challenge-based learning and problem-based learning.

Despite these terms being used fairly liberally (along with inquiry-based learning), I don’t seem to often come across material that explores the differences or similarities between these terms. I mean, I’m sure we could all take guesses about it, based on what we know about the words chosen; what is a project? what is a challenge? a problem? an inquiry?

Well, while you’re pondering it all, here is some more information to add to the learning theory soup.

States of Play

An overview of the elements of play presented by the National Institute for Play (based in California) outlines seven “patterns of play”:

- attunement play

- body play and movement

- object play

- social play (including ‘rough and tumble’ play and ‘celabratory’ play)

- imaginative and pretend play

- storytelling-narrative play

- transformative-integrative and creative play

And here is a really excellent TED Talk by Stewart Brown, who argues the physiological importance of play:

After listening to Stewart’s TED talk, the idea that I keep coming back to is this:

If the purpose is more important than the act of doing it, it’s probably not play. (Stewart Brown, TED Talk 2008, at ~6 mins)

Which begs the question: by trying to pin down a definition of ‘play-based learning’ to use in my curriculum theorising, am I contributing to WRECKING IT?

Play in the curriculum

In my quest for answers I came across some interesting material relating to motivation and mastery.

This puts me back into territory that is a little bit psych-y, and I know such approaches don’t always sit well with post-structuralist curriculum types like myself. But I resist that 😉

Writer and researcher Katherine Cushman lead a Practice Project for the non-profit group ‘What Kids Can Do’ (http://firesinthemind.org/about/) asking the question ‘what do kids already know about and do well?’.

When adults openly explore our genuine questions about getting to mastery—and include young people’s knowledge and experiences in that exploration—we model the expert’s habit of taking intellectual and creative risks. We demonstrate that we, too, always have things we need to understand better, and things we need to practice. We teach kids to approach any lack of understanding as a puzzle: stretching the limits of their competence, continually testing new possibilities and seeing how they work out. As they expand their knowledge and skills, young people, like us, will discover even more challenging puzzles they want to tackle—not just outside school, but as part of it. (K. Cushman, Fires in the Mind p.10)

In light of this, play strikes me as a form of ‘intellectual and creative risk taking’, essential to building the habits of mind and the resilience needed to seek out and tackle new puzzles.

Who is playing?

Concepts about transformative play have been utilised by the Quest Atlantis project, and a lot of my Tweeps are currently going bananas for Minecraft. These are rich sites and communities tapping into discourses about educational play.

However, I rarely hear any critical views about play or games, and I guess that’s what makes me itch to interrogate this field.

The reflexive dilemma

Listening to a talk by Julian Sefton-Green during his recent visit to QUT, I was conscious of the points he made about the field of ‘out of school learning’, which often involves elements of play.

His research has found distinctions between school and out-of-school learning tended to set up binaries that actually maintained the boundaries around ‘official’ curriculum, and other project and play based activities happening outside of schools (the binary of formal and non-formal learning, for example). His review of the literature showed how debate about not-school environments in the UK is often bound up with techno-utopianism and generalisations about the public school system.

In relation to this, he poses the ‘reflexive dilemma’ that we face in thinking about all of this. That is, the more we reflect on learning experiences, the more we formalise them. In our quest to ‘optimise’ all learning experiences, the learning is more carefully arranged and disciplined.

Which brings me right back to that TED talk – by naming ‘play based learning’ and trying to give play an official role in curriculum, do we run the risk of ruining play? Will the act of ‘doing play’ become just another ‘strategy’ for learning?

In short, how can we develop play as a habit of the mind without over thinking it and taking the fun out of the act of play? And, will defining the difference between all of the different PBLs etc help us in this endeavor, or just get in the way by drawing boundaries that don’t need to be there?

Pedagogy or assessment – what comes first in PBL?

Posted by kmcg2375 in education, reflections, research, university on September 5, 2011

So many things to blog about at the moment…transmedia and transliteracy, the Gonski review of school funding…but in the thick of Semester 2 teaching I find myself inexorably drawn back to curriculum studies.

And goddess, please bless Bianca for coming through with a new blog post about Project Based Learning (PBL) to stimulate my thinking this week!

I have been trying to work out how to formally incorporate PBL into the structure of my unit English Curriculum Studies 1. This week I think I have a solution, which I’ll outline below. But first, to answer Bianca’s question: when I proposed this structure in a comment on her blog she asked:

Did you design the assessments or the pedagogy first?

And that question, RIGHT THERE, is our chicken and egg, am I right?

Because, as Bianca rightly points out, school teachers find it very challenging to engage in “inherent ‘assessment for learning’ within the rigid ‘assessment of learning’ framework already in place”. So, while it might seem logical that your pedagogy will determine your assessment, the ‘reality’ of teaching and learning puts this possibility beyond reach for most.

Because, as Bianca rightly points out, school teachers find it very challenging to engage in “inherent ‘assessment for learning’ within the rigid ‘assessment of learning’ framework already in place”. So, while it might seem logical that your pedagogy will determine your assessment, the ‘reality’ of teaching and learning puts this possibility beyond reach for most.

For some schools their ‘rigid assessment of learning framework’ is tied to NAPLAN exams, for others it is focussed more on Year 12 exit credentials. And in schools that claim not to be driven by external assessments, rigid assessment frameworks can still be constructed by Heads of Department (or others) who seek to place multiple additional constraints on teachers’ planning (e.g. “you MUST have a half yearly exam!”, “every Year 9 class must write an essay in term 1”)

The curriculum places constraints on assessment and pedagogy too, and I could start talking about the Australian Curriculum here. Instead I’ll show you what I built for the university semester context, and try to answer Bianca’s question from there.

Here is the draft outline for my unit in 2012:

- Weeks 1-4 focus: Inquiry based learning (assessment = critical/reflective essay) assessment as learning

- Weeks 5-7 focus: Project based learning (assessment = project + review of pedagogy used in class project) assessment for learning

- Weeks 8-9 focus: Challenge based learning (assessment = make lesson plans for English) assessment of learning

I can safely say that for this unit, I started with the assessment. Literally, I have adopted an existing unit with existing assessment pieces that take at least 6 months to get formally changed. So, while I have been tweaking each assessment piece each semester, I’ve been teaching it for 18 months now and a full overhaul of the structure is now needed to fully incorporate PBL and other constructivist approaches.

Beyond that initial point of departure though, I have oscillated between a pedagogy focus and an assessment focus each time I plan and change something in the unit.

I would say my major points of development around pedagogy and assessment were:

- Reviewing the balance of assessment FOR learning and OF learning in the existing unit. In the university context it is only possible to mandate summative assessment…so I had to reconsider my approach to build a learning environment where the learning process was valued.

- Reviewing the first summative assessment, which was a critical essay, gave me the idea to make the relevance or ‘connectedness’ of the opening weeks of the unit more apparent. Students now do a range of inquiry-based activities to help them engage in the scholarly material, motivated by the need to interrogate their own perspective.

- Activities planned for the first few weeks of the unit were redesigned around a new assessment that focussed on the students personal teaching philosophy. This increased the potential of the assessment to be FOR learning, I thought.

- Teaching the new opening to the unit was really affirming, but showed up the weaknesses in the pedagogy of weeks 5-7. A PBL approach was therefore introduced to ‘liven up’ this part of the unit. This coincides with the time in semester when students begin having heaps of assignments due, and I felt they needed a pedagogical experience that was less ‘intense’, and enjoyable enough to get them through the ‘hump weeks’!

- The PBL appraoch worked really well, but the students put a lot of work in that wasn’t rewarded in assignment grades. So I am now redesigning assignment 2 to include ‘project participation’ criteria so students can get their work on this counted in their final grade.

- aaand…MOST recently: because the final assessment of creating alesson plans really has proven a ‘challenge’, I’m going to use this to explore Challenge based learning. I see this as being the same as Project based learning, but where the outcome does not have to be presentation to an audience. Instead, the project outcome must ‘meet the challenge’. Think Mythbusters 🙂

You can see how thinking about assessment and pedagogy are totally bound together – thinking about one always raises questions for the other. Or, it should!

I’m still searching for material that can explain the realtionship between Inquiry, Project and Challenge based learning. I’ve tried to use them here in a complementary way, but tbh it’s been tough to find sources that relate the approaches to one another. I started off this process thinking they were slightly interchangable. Now I can see that each one is informed by a respect for ‘learning by doing’, but has its own unique flavour. But are these three the only three? Do they sit in a hierarchy of some kind? Are there other ‘Something-B-Ls’ out there that I don’t know about??

Who knows.

If you do, please add a comment! (I hope this helps someone out there!)

Gamification and Behaviourism

Posted by kmcg2375 in education, politics, research, technology, video games on August 12, 2011

I dig gamification. I also dig Games Based Learning (GBL).

But sometimes when I’m watching these concepts get promoted, big alarms go off in my head.

Take a look at this list of some key elements of gamification:

- Points

- Badges

- Levels

- Challenges

- Leaderboards

- Rewards

- Onboarding

Doesn’t this remind you of anything? Add that together with our enthusiastic embrace of digital and electronic teaching, and the ‘games & machines’ motif becomes really familiar. I’m thinking Skinner, and Behaviourism, and Pavlov’s dog…which means that we need to think about the ethics of gamification, stat.

Why it doesn’t matter that NSW keeps losing the State of Origin…

…GO YOU GOOD THINGS!

NSW deals national curriculum a blow

Adam Bennett (Sydney Morning Herald) August 9, 2011

[NSW Education Minister] Mr Piccoli on Tuesday announced the state government would postpone the implementation of the national curriculum by 12 months because of a lack of commonwealth funding and uncertainty about the content.

NSW will now introduce the Australian curriculum in English, Maths, Science and History in 2014, with the planning phase beginning in 2013.

Mr Piccoli said that while the NSW government remained committed to the reforms, schools couldn’t prepare for its introduction in 2013 with funding issues still unresolved and the curriculum’s content not known.

“Schools needed to know in June of this year precisely the content of the national curriculum and to know that there were funds available for professional development,” he told reporters in Sydney.

“The final document won’t be signed off until at least the ministerial council meeting in October, and that simply does not give the schools in NSW and the more than 100,000 teachers the opportunity to receive the professional development, and to be in a position to implement the national curriculum in 2013.”

Thank you New South Wales for Standing Up and Putting Your Foot Down, while the rest of the educrats and Ministers around this country smile and nod and agree to bring in a curriculum overnight when they Quite Frankly Should Know Better.

That’s MY State of Origin!

Finding Arthur Applebee

Posted by kmcg2375 in education, english, Lit_Review, research on July 31, 2011

It’s only now that I’m finalising my thesis that I’m finding the work of U.S. curriculum studies researcher Arthur Applebee.

His works include his first book Tradition and Reform in the Teaching of English: A History (1974) and the later Curriculum as Conversation (1996). These are focussed on reviewing the teaching of English in the United States, but the historical connections he makes are invaluable to all of us in the field.

Here’s a clip from Curriculum as Conversation:

The medium is the message

Posted by kmcg2375 in books, digital storytelling, education, english, Lit_Review, research, technology on June 30, 2011

“The medium is the message” is a phrase coined by Marshall McLuhan meaning that the form of a medium embeds itself in the message, creating a symbiotic relationship by which the medium influences how the message is perceived. (from Wikipedia)

The more I think about this issue of medium, the more unsatisfied I am with the way that medium of production is dealt with in the English curriculum.

While English teachers continue to be led by debate over the definition and role of Literature in English, and over the best way to teach language, questions of medium have been significantly sidelined.

It also seems clearer to me now why subjects like Drama and Media (content areas that technically sit under the umbrella of English, if you accept that English is a study of how meaning is made through language and texts) go off and take up their own space in many curriculum. It’s not just because those fields have their own traditions and pedagogies that need space, or because they have industries that create an economic drive for the subjects to continue. It’s also because those field require keen attention to production elements, including issues of medium.

Little wonder that Drama, which often deals with live performance of language, dies a slow death in English classrooms where the curriculum is still dominated by print literacy.

Little wonder that we still can reconcile the gulf between ‘literary’ and ‘digital/electronic’ texts in the Australian curriculum (medium is not a genre!)

To move anywhere with this line of thinking will require some careful thought about the overlap between the words:

- media as-in-the-artisitic-means-of-production and

- Media as-in-the-field-of-media-studies.

Thanks to carolyn for stimulating my thinking on this. Connecting the concept of medium back to the concept of narrative helped the penny drop today!

Change agents – Pirates vs Ninjas

Posted by kmcg2375 in education, social media, technology, university on March 22, 2011

I was prompted by Binaca today to look for an old post of mine on giving feedback to students. In my search I was delighted to find it had been almost exactly one year since I wrote this post about the tension caused by curriculum change, especially in regards to integrating ICTs:

Let’s make sure we’re applying the ‘too much is too much’ rule across the board, and not just as an excuse/a reason for neglecting the new. If what we mean is ‘we haven’t had enough PD to use this right’ then by all means say that. But there are some things that would be good to drop out of our current practice to make room for the new. One thing that we know about teaching is that no matter what you are taught to do, as a teacher you will instinctively model your practice on the teaching you received at school. Fighting against this instinct takes concentration, and learning about new practices and tools takes a lot of work. Because of this, teachers who are embracing technology are feeling increasingly overloaded and burnt out – this is the real problem that needs managing.

In a later post I tried to be more generative than reflective by reframing the process of change, suggesting that:

…as educational leaders, if we want to help people come to terms with change and embrace it, then we need to recognise and validate their desire to stick with ‘the known’…Recognising that people are resisting change because they feel disempowered helps us to employ methods that give power back.

These lines of thinking manifested in the lecture I gave today to preservice English teachers on how to navigate change amidst all of the ‘theories of text and response’ that they had learned so far.

You may be pleased (dismayed?) to watch how I liken the characteristics of change agents to either the NINJA or PIRATE side of the popular theoretical battle, Pirates vs Ninjas 😀

I think I am mostly pirate!

Good News Day

This front page made me smile so much yesterday I broke my usual rule and bought The Australian:

PRIVATE SCHOOLS’ FURY OVER MYSCHOOL WEBSITE

Turns out the poor buggers have found some inaccuracies in the way their finances are reported. It makes it look like they are getting paid WAY too much money for the services they provide, or something totally unbelievable like that.

I say: suck it. Where were you last year when NSW public school teachers and unions were the only ones out there willing to put their neck on the line to criticise the MySchool website? Sitting quietly on their hands and calling us whingers, that’s where.

STATE REJECTS PM’s CURRICULUM AS SUBSTANDARD

Which state you ask? Oh, that’d be NSW. Again. As far as I can see, the only state with the balls to take a stand against ACARA. Again.

Now, I realise full well that teachers in every state and territory think that their curriculum is ‘the best’. But that’s not what this is actually about. This is not just about some east-coast superiority complex. This is about (in the case of English, at least) the inadequacy of the curriculum on offer.

I love my new home in Queensland, but for sheer determination to kick against the pricks, I am proud to say ‘go the Blues!’ On National Curriculum issues, NSW is proving well and truly to be the big sister of Australia – she might not always be right, but at least she’s brave enough to fight for what she thinks is right (inaccurate newspaper reporting be damned).

SIDDLE BLOWS ENGLAND AWAY WITH HATTRICK

OK, so any real Australian knows that this was the only real story of the day.

If you don’t know what a hattrick in cricket is, it’s when a bowler gets three batsmen out in a row. It’s very hard to do. Since the start of the Ashes in 1877 there have only been eight other hattricks, making Siddle’s the ninth. And it was his birthday!

What a good news day!

English: I would call it ‘Language Arts’

Wouldn’t it be lovely if, while we are in the process of drafting an Australian National Curriculum, we could ditch the subject title ‘English’?

I mean, what reasons do we have for keeping the name? I know it represents an important connection to our English/colonial literary heritage, but does anyone really think that changing the name of the subject is going to slow the study of Shakespeare, Keats or Austen? And I realise that some people will be saying ‘but it is about studying the English language, hence ENGLISH!’ But surely what we do in this subject is about more than studying language…just like the study of ‘Visual Arts’ is about more than studying design elements.

I see a lot of room for connection between subjects like English, Visual Arts and Music. To me, these school subjects all have in common the study of

- how meaning is made using signs/symbols

- how people express themselves

- how to reflect on expression to better understand the world

Currently the increase in multimodal texts has meant the expansion of English, and some would say the study of sounds and visual ‘language’ in English constitutes a colonisation of sorts…English seems to some to be taking over the material of other subjects! On this point I disagree – there remains in English the special project of studying works/pieces/texts that are grounded in WORDS. The fact of the matter is that many forms of expression that use words also engage with other sign systems. Words are spoken, and heard. They are written and seen. They are illustrated. They are enacted. The subject title ‘English’ just doesn’t encapsulate all of this for me.

The other problem with the English subject label is that it lacks an emphasis on the creative element of studying words. It would be inconceivable that subjects in the creative arts – Visual Arts, Music, Drama etc – would focus on learning technical aspects of their craft at the expense of engaging in art-making. Yet, this scenario is all to prevalent in contemporary English classrooms. We study novels, poems, films, as well as technical aspects of language, but the actual crafting of original texts is neglected. While Major Works in the creative arts subjects constitute 50% of their respective HSC courses, English only requires students to complete one out of six exam sections on creative writing, and this is done as a first draft in 40 minutes 😦 Although ‘Composing’ is supposed to make up 50% of the English course, much of this is done in the form of ‘composing’ texts such as essays to prove what has been learned about other people’s texts!

It is because of this that I would love to see English renamed ‘Language Arts’, and the processes of responding and composing renamed studies of ‘theory’ and ‘practice’.

The study of words should be a joy. For this to occur, students who are learning about words must also get elbow deep in making their own texts. It should be messy, experimental, personal and forgiving practice – like what you see in an Art room. And if we can teach students about words in a way that helps them to express themselves and understand the world around them, they will want to learn more. Of this I am sure.

Defining ‘multimodal’

Reading the Draft Australian Curriculum for English (‘DACE’…?) I can see that confusion over the meaning of ‘multimodal’ text is about to cause English teachers some major problems.

My understanding is that when we say a text is ‘multimodal’, we mean that the audience participates in the text’s creation. This is the definition I would say that academics and practitioners in the field of English curriculum would use; consider this explanation by Anastopoulou, Baber & Sharples:

Multimodality is based on the use of sensory modalities by which humans receive information. These modalities could be tactile, visual, auditory, etc. It also requests the use of at least two response modalities to present information (e.g. verbal, manual activity). So, for example, in a multimodal interaction a user may receive information by vision and sound and respond by voice and touch. Multimodality could be compared with ‘unimodality’, which would be based on the use of one modality only to receive or present information (e.g. watching a multimedia presentation and responding by pressing keys).

…but that’s not the definition that ACARA are going with.

The definitional confusion between terms like multimodal, multimedia and media has been around for a while, and speaks to the significant changes in what is considered core content in English brought about by the rise in visual and especially digital texts. We are very familiar with the concept that language can be spoken, written or heard…but when it comes to texts that combine these modes, things are still a little muddled.

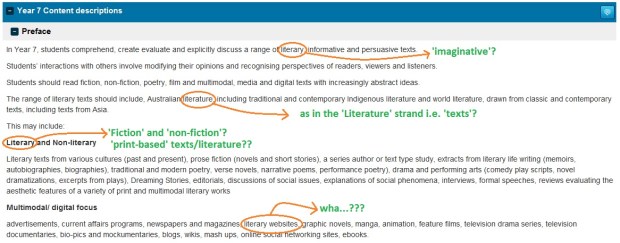

Please take a moment to check out, for example, the preface for the Year 7 section of the DACE (click the image below and get ready for your head to spin):

See what I mean?

In this Preface to the curriculum content descriptors multimodal texts seem to be pitted against texts that are ‘literary’ (which creates even more confusion as the definition of literary appears to change with each new use). I can appreciate that the ACARA curriculum writers have had to avoid using the word ‘text’ because of the political beat up the term has received in recent years from certain op-ed writers in certain newspapers. That is why this new curriculum has reverted to the more traditional term Literature – and it is because of this change that we are now supposed to say, it seems, ‘literary text’.

But now check out the etymological shenanigans that take place in the content descriptors of the Literature strand:

Oh brother. The constant reference to ‘literary texts’ is supposed to be a nod to the strand content being described as ‘Literature’. But this is ultimately VERY confusing, as ‘literary’ texts are separated from ‘non-literary’, digital’ and ‘multimodal’ texts in the Preface. There result is that there is no sense in this strand of multimodal texts being included.

The term ‘literary’ is also conflated with ‘fiction’, and what are really language elements are referred to as literary elements. In ‘Discussing and responding’ the term ‘text’ makes it in unscathed – which just goes to show that the word does make sense and can be used. The term ‘text’ is highly appropriate for collectively describing all works of language art, and recognises that the works we study can be written, spoken, aural, or a combination of these. The term ‘literary texts’ is stupidly redundant, but I’d be happy to get on with using it to placate the punters, if only it were used consistently and provided scope for the study of a broad range of texts! Which brings me back to multimodality…

In the NSW English syllabus, students engage in what we call a range of language modes. These are: speaking, writing, representing, listening, reading and viewing. So ‘multimodal’ could reasonably be taken to mean ‘using more than one language mode’. This would make film, picture books and digital stories (which use a combination of visual and written language) and many other forms of text multimodal. OK, I can work with that.

But another thing we do in NSW English 7-12 is differentiate between the activities of composing (which involves text ‘making’ or ‘creation’, not just ‘writing’) and responding (a broader term than ‘reading’ which encompasses the ‘reception’ of all kinds of text). These activities are viewed as always interrelated in some way, but I would say that it is only when text explicitly invites the audience to participate in the text (e.g. in video games, virtual reality, and participatory narratives such as Inanimate Alice) that the term multimodal should really be applied. If I’m going to give up the term ‘multimodal’ to the meaning of ‘using more than one language mode’, then I’m going to need a NEW WORD that I can use when I mean ‘texts that the audience helps to construct’.

Currently this recognition of interactivity, and of the interplay between responding and composing, is severely lacking in the DACE.

[ED: Angela Thomas has helped me to clarify my thinking around this, and suggests that students could refer to the ‘cline of interactivity‘ for texts that invite participation. My thoughts on multimodality have been developed here. June 2010]

If you are an English teacher and haven’t yet responded to the consultation on the Draft Australian Curriculum, I implore you to log on to the ACARA site and say something about these contradictory and frankly bizarre definitions. I can’t be the only one who feels like the curriculum writers just didn’t use a glossary!

Faced with the prospect of a shiny new curriculum that is supposed to be clarifying professional meanings and terminology for all teachers, students and parents across the nation, these definitional conflicts are something that must be sorted out before we go any further. Agreed?

Recent Comments