Archive for category english

Helping teachers to explore multimodal texts

This extract from a recent article in the journal Curriculum Leadership (Vol 8 Issue 16) would make an ideal addition to the Australian Curriculum for English, from K-12:

What are multimodal texts?

A text may be defined as multimodal when it combines two or more semiotic systems. There are five semiotic systems in total:

- Linguistic: comprising aspects such as vocabulary, generic structure and the grammar of oral and written language

- Visual: comprising aspects such as colour, vectors and viewpoint in still and moving images

- Audio: comprising aspects such as volume, pitch and rhythm of music and sound effects

- Gestural: comprising aspects such as movement, speed and stillness in facial expression and body language

- Spatial: comprising aspects such as proximity, direction, position of layout and organisation of objects in space.

Examples of multimodal texts are:

- a picture book, in which the textual and visual elements are arranged on individual pages that contribute to an overall set of bound pages

- a webpage, in which elements such as sound effects, oral language, written language, music and still or moving images are combined

- a live ballet performance, in which gesture, music, and space are the main elements.

Multimodal texts can be delivered via different media or technologies. They may be live, paper, or digital electronic.

The article, by Michele Anstey and Geoff Bull, outlines ways to help support students’ facility with multimodal texts, and ideas for commencing a professional learning process to engage with multimodality in more sophisticated ways.

If ACARA were to adopt this framework for modality (including the terminology of the ‘technology’ of ‘delivery’, and the broad categories of live, paper and digital electronic production) I think the Curriculum would be headed in a much more generative (and logical!) direction.

Ave Narrative…

OK, so I’m not Catholic.

But I feel Ave Maria is an apt musical choice today with ACARA’s announcement that the writing style to be tested in NAPLAN will no longer be Narrative, but Persuasive.

You can get the information here: http://www.naplan.edu.au/writing_2011_-_domains.html

Let me say straight up that I love persuasive writing. I love essays, I love speeches, I love editorials. I love persuasive language. One of my favourite units to teach is our Year 11 unit ‘Voices of Protest’ where students explore persuasive writing forms and techniques through a close study of a speech and related protest poems.

What I don’t love is the way that Stage 6 English buries imaginative writing within an Area of Study and Modules that are in reality oriented toward responding to the texts of others.

I also don’t love the fact that in the HSC, students in the mandatory 2 unit English are only examined on imaginative writing in any form in ONE out of the SIX exam sections. The way I see it, both in my teaching and through everything I have researched so far, doing so constitutes a ‘hidden curriculum’ that devalues student imagination and decreases the time teachers can spend on creative language skills.

At least we had NAPLAN, eh?

At least it was there as an externally managed assessment of student literacy and language that signalled the importance of the creative. The importance of imagination. The importance of the lyrical, the figurative and of imagining other worlds.

Not any more.

And so the message is clearer than ever – essays rule the roost. Get your kids started early on perfecting their persuasive writing, lest they struggle with HSC exams!

I challenge anyone from ACARA, or any of the Education Ministers who were at that MCEECDYA meeting where Narrative got the boot to explain that this decision had anything to do with ‘just mixing things up’. Anything whatsoever to do with providing a balance between persuasive and narrative writing in the assessment of curriculum. Because if they really do think so…well, it’s gotta be time to review the balance in the HSC, no?

AATE Annual Conference 2010

Posted by kmcg2375 in conferences, english, research on June 4, 2010

The full program for this years annual conference for English teachers in Australia can be found at:

http://www.englishliteracyconference.com.au/index.php?id=48&year=10

The conference is on this year in Perth from 4-7 July. I’ll be presenting a paper on the Monday about National Curriculum, based on my PhD research on curriculum change:

Getting comfy with the ‘new’: What we can expect to feel about curriculum change.

The National Curriculum will bring with it a host of challenges and problems that may leave us grieving for our familiar local curriculum. What can we expect to feel in this time of change? And what will the effects of this be on our beliefs, our pedagogy and our practice? How much of what we are already doing, really, are teachers expecting to be able to carry forward? It seems this point in curriculum history is an ideal spot for us to revisit and revise our curriculum philosophies, as well as our beliefs about the purpose and goal of teaching English.

Reflecting on the findings of my PhD research into the changes and innovations of the 1999 HSC English syllabus in NSW, in this paper I consider the processes by which teachers have coped with change. What is likely to make us uncomfortable in the National Curriculum for English? What have we already shown in NSW that we fear? The audience will be invited to consider their own philosophies, and begin preparing for change.

The 2011 conference will take place in Melbourne (in December), and the 2012 conference sees the conference returning to Sydney (in October).

English: I would call it ‘Language Arts’

Wouldn’t it be lovely if, while we are in the process of drafting an Australian National Curriculum, we could ditch the subject title ‘English’?

I mean, what reasons do we have for keeping the name? I know it represents an important connection to our English/colonial literary heritage, but does anyone really think that changing the name of the subject is going to slow the study of Shakespeare, Keats or Austen? And I realise that some people will be saying ‘but it is about studying the English language, hence ENGLISH!’ But surely what we do in this subject is about more than studying language…just like the study of ‘Visual Arts’ is about more than studying design elements.

I see a lot of room for connection between subjects like English, Visual Arts and Music. To me, these school subjects all have in common the study of

- how meaning is made using signs/symbols

- how people express themselves

- how to reflect on expression to better understand the world

Currently the increase in multimodal texts has meant the expansion of English, and some would say the study of sounds and visual ‘language’ in English constitutes a colonisation of sorts…English seems to some to be taking over the material of other subjects! On this point I disagree – there remains in English the special project of studying works/pieces/texts that are grounded in WORDS. The fact of the matter is that many forms of expression that use words also engage with other sign systems. Words are spoken, and heard. They are written and seen. They are illustrated. They are enacted. The subject title ‘English’ just doesn’t encapsulate all of this for me.

The other problem with the English subject label is that it lacks an emphasis on the creative element of studying words. It would be inconceivable that subjects in the creative arts – Visual Arts, Music, Drama etc – would focus on learning technical aspects of their craft at the expense of engaging in art-making. Yet, this scenario is all to prevalent in contemporary English classrooms. We study novels, poems, films, as well as technical aspects of language, but the actual crafting of original texts is neglected. While Major Works in the creative arts subjects constitute 50% of their respective HSC courses, English only requires students to complete one out of six exam sections on creative writing, and this is done as a first draft in 40 minutes 😦 Although ‘Composing’ is supposed to make up 50% of the English course, much of this is done in the form of ‘composing’ texts such as essays to prove what has been learned about other people’s texts!

It is because of this that I would love to see English renamed ‘Language Arts’, and the processes of responding and composing renamed studies of ‘theory’ and ‘practice’.

The study of words should be a joy. For this to occur, students who are learning about words must also get elbow deep in making their own texts. It should be messy, experimental, personal and forgiving practice – like what you see in an Art room. And if we can teach students about words in a way that helps them to express themselves and understand the world around them, they will want to learn more. Of this I am sure.

Defining ‘multimodal’

Reading the Draft Australian Curriculum for English (‘DACE’…?) I can see that confusion over the meaning of ‘multimodal’ text is about to cause English teachers some major problems.

My understanding is that when we say a text is ‘multimodal’, we mean that the audience participates in the text’s creation. This is the definition I would say that academics and practitioners in the field of English curriculum would use; consider this explanation by Anastopoulou, Baber & Sharples:

Multimodality is based on the use of sensory modalities by which humans receive information. These modalities could be tactile, visual, auditory, etc. It also requests the use of at least two response modalities to present information (e.g. verbal, manual activity). So, for example, in a multimodal interaction a user may receive information by vision and sound and respond by voice and touch. Multimodality could be compared with ‘unimodality’, which would be based on the use of one modality only to receive or present information (e.g. watching a multimedia presentation and responding by pressing keys).

…but that’s not the definition that ACARA are going with.

The definitional confusion between terms like multimodal, multimedia and media has been around for a while, and speaks to the significant changes in what is considered core content in English brought about by the rise in visual and especially digital texts. We are very familiar with the concept that language can be spoken, written or heard…but when it comes to texts that combine these modes, things are still a little muddled.

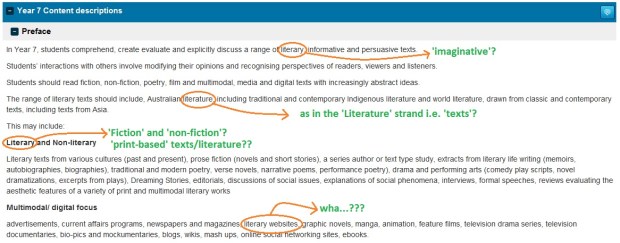

Please take a moment to check out, for example, the preface for the Year 7 section of the DACE (click the image below and get ready for your head to spin):

See what I mean?

In this Preface to the curriculum content descriptors multimodal texts seem to be pitted against texts that are ‘literary’ (which creates even more confusion as the definition of literary appears to change with each new use). I can appreciate that the ACARA curriculum writers have had to avoid using the word ‘text’ because of the political beat up the term has received in recent years from certain op-ed writers in certain newspapers. That is why this new curriculum has reverted to the more traditional term Literature – and it is because of this change that we are now supposed to say, it seems, ‘literary text’.

But now check out the etymological shenanigans that take place in the content descriptors of the Literature strand:

Oh brother. The constant reference to ‘literary texts’ is supposed to be a nod to the strand content being described as ‘Literature’. But this is ultimately VERY confusing, as ‘literary’ texts are separated from ‘non-literary’, digital’ and ‘multimodal’ texts in the Preface. There result is that there is no sense in this strand of multimodal texts being included.

The term ‘literary’ is also conflated with ‘fiction’, and what are really language elements are referred to as literary elements. In ‘Discussing and responding’ the term ‘text’ makes it in unscathed – which just goes to show that the word does make sense and can be used. The term ‘text’ is highly appropriate for collectively describing all works of language art, and recognises that the works we study can be written, spoken, aural, or a combination of these. The term ‘literary texts’ is stupidly redundant, but I’d be happy to get on with using it to placate the punters, if only it were used consistently and provided scope for the study of a broad range of texts! Which brings me back to multimodality…

In the NSW English syllabus, students engage in what we call a range of language modes. These are: speaking, writing, representing, listening, reading and viewing. So ‘multimodal’ could reasonably be taken to mean ‘using more than one language mode’. This would make film, picture books and digital stories (which use a combination of visual and written language) and many other forms of text multimodal. OK, I can work with that.

But another thing we do in NSW English 7-12 is differentiate between the activities of composing (which involves text ‘making’ or ‘creation’, not just ‘writing’) and responding (a broader term than ‘reading’ which encompasses the ‘reception’ of all kinds of text). These activities are viewed as always interrelated in some way, but I would say that it is only when text explicitly invites the audience to participate in the text (e.g. in video games, virtual reality, and participatory narratives such as Inanimate Alice) that the term multimodal should really be applied. If I’m going to give up the term ‘multimodal’ to the meaning of ‘using more than one language mode’, then I’m going to need a NEW WORD that I can use when I mean ‘texts that the audience helps to construct’.

Currently this recognition of interactivity, and of the interplay between responding and composing, is severely lacking in the DACE.

[ED: Angela Thomas has helped me to clarify my thinking around this, and suggests that students could refer to the ‘cline of interactivity‘ for texts that invite participation. My thoughts on multimodality have been developed here. June 2010]

If you are an English teacher and haven’t yet responded to the consultation on the Draft Australian Curriculum, I implore you to log on to the ACARA site and say something about these contradictory and frankly bizarre definitions. I can’t be the only one who feels like the curriculum writers just didn’t use a glossary!

Faced with the prospect of a shiny new curriculum that is supposed to be clarifying professional meanings and terminology for all teachers, students and parents across the nation, these definitional conflicts are something that must be sorted out before we go any further. Agreed?

Civilisation and culture

A recent post of Darcy’s got me thinking a bit more about the questions of ‘civilisation’ and ‘culture’, in particular about how these relate to my work as an English teacher.

One aspect of this is that the increase in use of technology has also brought an increase in people’s ability to create and publish their own texts. Notions of the importance of the traditional, western literary canon are being challenged. More and more students are approaching me, asking if I have read/seen/listened to a particular book/film/piece of music, and I am confounded. The 30 students sitting in front of me in the class are exposed to so much in their cultural world, and I have no hope of claiming expertise on such a diverse range of cultural artefacts.

This stands in contrast to some of the notions I had about being ‘cultured enough’ to be a ‘proper English teacher’ before I started university. I recall the summer holidays after year 12 when I found out I had gotten into a Bachelor of Education at Sydney University. I was going to be an English teacher – hooray! But there was also a dark side: now I was going to have to read friggin Lord of the Rings. And so I dutifully did. Later, in university, I also subjected myself to an entire box set of Jane Austen for the same reason – if I was going to be an English teacher, I was going to have to ‘know my stuff’.

Don’t get me wrong – I am glad for pushing myself to extend my reading to the English curriculum ‘canon’. It turned out that I loved Lord of the Rings (my how I had grown since year 9 when I hated The Hobbit with a passion) and reading it opened a whole new world for me, whetting my appetite for the entire Fantasy genre. A couple of the Austen’s were OK too – though Emma did become the first book that I ever didn’t finish (I’m a staunch book finisher) I was glad to discover that I didn’t care for pre-20th century stories about genteel English living, no matter how satirical they were intended to be. So, reading Austen taught me not to fear the canon, and not to feel inadequate in it’s shadow.

Now, this post is meandering a little, but bear with me…

The extracts that Darcy posted from Kenneth Clark‘s television series Civilisation included a few ideas that I found very useful for reflecting on my own growing understanding of the relationship between society and culture. In particular I noted these down:

Great works of art can be produced in barbarous societies – in fact, the very narrowness of primitive society gives their ornamental art a peculiar concentration and vitality.

Well, I certainly wouldn’t say that England in the 1800s was primitive! But could it be that people become besotted by this period of Literature because of its narrowness, because it is define-able and knowable? Because its concentration lends it a vitality that is found wanting in contemporary culture which is so diverse and dispersed? Is this also what makes Shakespeare so attractive?

We are not entering a new period of barbarism. The things that made the dark ages so dark [were] the isolation, the lack of mobility, the lack of curiosity, the hopelessness…

This is an astute observation, and one that could perhaps quell any fears that people may have about technology, postmodernism, cultural relativism or whatever [insert social ill of choice here] posing a threat to civilisation and culture. We live in a world that is more connected than ever before, and the growth in cultural production is surely an expression of our curiosity and willingness to engage with the world. This doesn’t mean we should hate the traditional canon. However…

One mustn’t overrate the culture of what used to be called ‘top people’ before the wars. They had charming manners, but they were as ignorant as swans…the members of a music group or an art group at a provincial university [today] would be ten times better informed, and more alert.

Now Clark is really speaking my language. Because, as I discovered when I made myself read explicitly canonical texts, I’m not the canon hater that I thought I was as a teenager. On the contrary, even though I didn’t enjoy reading Austen, I found great value and pleasure in developing my knowledge of the way texts that had been deemed ‘the best’ influenced culture that superseded it. And, as with Shakespeare, I now delight in researching and thinking about how texts reflect their social and political context (this makes me an excellent teacher of Advanced HSC Module B Critical study, in my very humble opinion).

The contribution I would like to make to this assemblage of interesting texts about civilisation is Alain de Botton’s book and documentary film about Status Anxiety. Here is the introduction to the documentary:

de Botton argues that increases in living standards have not increased our levels of happiness, due to our anxiety about our social status. To return to one last observation from Clark:

The children of [our] imagination are also the expressions of an ideal.

I believe that the current boom in the production of cultural artefacts expresses an ideal that can lead us away from status anxiety – where something like the literary canon is valued, but is knowledge of it is not misused as a demarcation of status. With a wider range of cultural expression being valued, our fears about being outed as ‘not knowing everything’ fade away as people recognise the impossibility, and folly, of this desire. I also am hopeful that our increasing tendency to engage with culture as produsers reflects a growth in ideals such as respect for diversity in creative expression and authentic engagement with community.

Of course, there is another angle that we could engage in here – there is a famous quote that I can’t remember, something about civilisation being measured by how well we look after the poor…if you made it to the end of this post 😉 and you know the one I mean, can you add it as a comment? In this vein I encourage readers to revisit a song from 1992 (a golden year for music!) where Mr Wendal serves as an example of the plight of the homeless:

Civilization, are we really civilized? Yes or no ?

Who are we to judge ?

When thousands of innocent men could be brutally enslaved

and killed over a racist grudge.Mr.Wendal has tried to warn us about our ways

but we don’t hear him talk…

…but that is food for a whole different post.

A personal response to technology hating

Posted by kmcg2375 in english, online tools, personal, social media, technology on March 17, 2010

This is a post for my friend Shaun, but I hope it’s something you all can use.

Shaun is a top bloke. He’s an English teacher who has a deep passion for literature and from what I can tell a real knack for sharing this with his students. His students get great results at assessment time. He’s warm, funny, relatable and engaging.

But, in a brief chat about another blogger’s controversial anti-technology post, it was clear that Shaun was not enthusiastic about digital learning.

In fact, he despises it. And also has had such bad experiences that he now doesn’t trust teachers who use it.

So…what to say to my friend who is in the position of already being a great teacher getting great results?

How to convince him that digital learning is more than fancy icing on his otherwise tasty, filling and nutritional educational cake?

I thought that this task might call for a personal story.

ABOUT ME: I am an English teacher who has always loved English. As a child and teenager, reading was like breathing to me – not just ‘part of life’, but an urgent necessity. In school I excelled at debating, and public speaking. For my HSC I studied as much English as I could – 2 unit Related plus 3 unit English. I loved essay writing, adored my English teachers, and was in my element during teacher lectures that were accompanied by class discussion. My UAI was in the mid 90s. I was a successful English student.

MY CONFESSION: While all of the above is true, it is also true that in year 9, for the first time, I did not read our class novel The Wizard of Earthsea. The teacher never knew, and my grades were stellar. Same again in Year 11 with The Scarlet Letter. Same again in HSC 3 unit English with Shakespeare’s The Tempest. And…same again with about a third of the books I was supposed to read for my University English courses, though in that arena my grades weren’t stellar…just above average.

Why do I make these confessions, horrible as they are for an English teacher?

Because when Shaun tells me that his students are all engaged with their learning without the use of technology, I can tell you from experience that they aren’t. Not authentically. Sure, they may gaze up in awe as he speaks passionately about the wonder of Hamlet, and they might have the skill to assemble good essays by aping the points brought up in class discussion. But I guarantee you Shaun, you are teaching at least some people just like me – people who slip under the radar due to their genuine love of English and their skill in using language, but who have the potential to be far more active in their learning.

The other reason I make these confessions is because arguments trying to promote the adoption of technology are often made with reference to engaging low-ability or disinterested students. And I support those arguments whole-heartedly – I have seen students, especially in the junior years, really turn their attitude around (especially in regard to writing) because the fun side and familiarity of using computers gave them the confidence and motivation to complete some work.

It is so much harder to convince teachers of ‘successful’ students that anything needs to change.

But (and Shaun this is my final point I swear!) not only does digital learning have the potential to increase student engagement at all levels due to its inclination toward communicative and collaborative learning practices, but I truly believe that neglecting the development of students’ digital literacy means that as teachers we are neglecting one of our key roles – the preparation of students to participate and engage fully with society, present and future. Technology isn’t going away. And English teachers that say ‘digital literacy is not my job’ would do well to remind themselves of the times when English teachers used to say ‘visual literacy is not my job’.

Times change. Media changes. Language changes. We must make sure our students are equipped to cope with this.

I would be most grateful if people could add comments to this post with their own personal success stories from English classrooms that have embraced technology, either in content, pedagogy or assessment.

We will not convince technology haters to change by telling them they are wrong, when their experience is to the contrary. We must do it by showing that we know about some amazing, engaging and powerful tools for achieving the outcomes they value and desire

…and that not all teachers using technology are merely doing so to look cool and get promoted 😉

Poems to Share

I love The Red Room Company. I started working with them last year, team-teaching poetry workshops with my year 10 class with poet Lachlan Brown. They are a group that loves sharing poetry with students and encouraging poetry writing as much as they love poetry itself!

Just now I have bought one of their new poetry teaching products, a card set called Poems to Share:

“Red Room Co. have teamed up with designers Corban & Blair to produce a beautiful card set featuring forty poems by contemporary Australian writers, along with writing exercises to get things moving.”

Red Room’s educational products are simply gorgeous.

Check them out and I know you’ll be adding them to your English faculty wish-list!

HSC English: Standard or Advanced?

Does your school offer both Standard and Advanced English courses for the HSC? How about ESL? Extension courses? If not – why not?

This is a question that has been debated over the past couple of days via email between members of the NSW English Teachers’ Association.

One member asked: Do you think it is wise to only offer the Advanced course to students? His school leaders have been advised that this will lead to higher ATAR scores for students at the school.

Here are some of the responses that were given via email in support of offering a diverse range of courses:

“The emotional pressure on students to learn (=compete and achieve) at an Advanced level was very detrimental in the schools I observed [that had decided to take away the option for Standard English]. Students’ self concept was very low for the bottom achievers in the Advanced stream, where in schools that also run Standard these kids might still perform lower, but they do so with the knowledge that they are in a different, less ‘academic’ course. Or, they find themselves at the top of the Standard course, and their self concept goes up. Offering Advanced-only also limits your capacity to differentiate learning for students, and it builds a distorted sense of entitlement and expectation among parents.”

“I have been discouraging some students who want to do Advanced. Last year when I arrived there seenmed to be some students who really should have taken Standard. Advanced can be soul destroying for them and can impede the progress of others.”

“I was also put under pressure [to increase] value-added – they argue that it is better for everyone to do Advanced because scaling boosts poor Advanced marks above good Standard marks and there may be an infinitesimally better uni ranking as a result. Whether this is actually the case or not is difficult to accurately gauge – there seems to be a lot of numerical flim-flam in the value-adding business. What is clear, however, is that students who struggle in Advanced and then withdraw from discussions and activities they feel are beyond them engage much more readily in Standard classes and find themselves enjoying English – heaven forfend!”

“I remember this type of pressure being applied at a previous school of mine – with the result of good Standard students being forced to do Advanced. That type of auditor-driven statistical analysis does not take into account the different kind of intellectual demands required to be a success in Advanced. At my current school, we have scaled back our Advanced classes because there were a number of students who were not suited to the contextual and researching demands of the Advanced syllabus – they were also not motivated readers”

Comments like these about student welfare were reinforced by teachers who had marked HSC English scripts and saw the outcome at the other end:

“Anyone who has marked Advanced will know there are many students out there who really should not have sat the course and would have been better off in Standard, where they would have had a much better opportunity to show what they knew and understood.”

“From the point of view of Advanced HSC marking, as many of you will have experienced, it is becoming more frequent to see that “poor child” who should have been advised to do Standard, often in the middle of a bundle of very competent students.”

Some teachers were in favour of pushing the Advanced course, and gave a mixture of pedagogical and statistical reasons for this:

“There is an ongoing debate about this in schools around mine. The pressure in schools is to achieve better than state mean and this can be easily achieved by encouraging students to do Standard rather than Advanced… I believe this is anti educational and think any student who is interested should have the opportunity to do the more interesting and challenging Advanced course. In terms of value added, this does us no favours [to push students into the Standard course]. Have a look at the difference in the curves for Advanced and Standard on the value added graph. Again I could easily make the actual course results look better by encouraging more students to do Standard and indeed have at times been pressured to do so. If you run the Advanced students against the overall English Value Added curve you get a different picture, however.”

“Our students do seem to get a strong sense of achievement from doing Advanced and actually engage well with texts which have not much relationship to their lives and experience. I agree that the Standard course is difficult since it is so language based and that is what students have trouble with…We don’t not offer Standard because it is too easy, but because our students can and do gain a great deal from the Advanced course and they value it. Or is it their parents? It just seems a pity that it is much more difficult to get very high marks in Standard than Advanced but it is historic. Remember why we brought in the common strand in the first place?”

Other teachers had arguments that spoke to the benefits of or need for the Standard course:

“What we have done is to present the challenges of the Advanced course to Year 10, outlining exactly the demands. We have also challenged Advanced students in Year 11 to consider seriously the demands of the course. This has meant many more “borderline” students have chosen Standard, either at the end of Year 10 or the end of the Preliminary course. As a result, we have had excellent Standard results from students who either deliberately chose to do Standard, or changed at the end of Preliminary when they struggled in the Advanced. The end result in those cases were very happy students and parents.”

“We certainly could not omit Standard from our curriculum, and fortunately, we are also able to maintain a more academic focus by running one advanced class. I hope that by doing that, we are meeting the diverse learning needs of the type of students who attend a school such as ours. I know this is not the same issue – but spare a thought for the large number of country schools who are struggling to offer courses and to do that, both Standard and Advanced are offered in the same room, sometimes with both 11 and 12 together as well. That is the only way their wide range of learning needs (for just a small number) can be met – either that, or Advanced is not offered at all.”

The role of school administrators in balancing the need for high results against student welfare and quality learning was also raised:

“Perhaps some school administrators need to be reminded of such determiners for course choice as “needs, interests and abilities of students”- not to mention their health and well-being. When there is a significant percentage of boarders these factors are particularly critical.”

“I think the whole debate is disgusting because no-one is talking about what we think students should know; i.e. education. Instead the whole debate seems to be about what puts the school in a better light statistically. Let’s worry about what our students should learn and where they are at, not what looks better for our school. How has this abominable shift in what teachers are thinking happened? Well we all know the answer to that: and the answer is not the National Curriculum.”

“It has been interesting to see two distinct problems emerge from this question and also dispiriting that in both cases it is all about perceived numerical and statistical success, with anti-educational ‘solutions’ imposed on English faculties from above.”

The debate itself was in fact surprising to some:

“Coming from an area of the state that is maybe too far in the bush, I have never realised that this would be an issue. I know that some schools, for very good reasons such as being selective, have none or very few Standard students, and that is just a given, but I would have thought that the majority of schools in the state would not fall into that category. I guess that might be blissful lack of knowledge or awareness on my part!”

I’d (we all!) be interested to hear how other schools and English faculties are approaching this question.

When I put the question out to Twitter this afternoon, this is what tweeple had to say:

“I think English should be an elective course. If they haven’t got it by year 10 why go further?”

“Really? [that not all states have mandatory English] so only NSW is dumb enough to think senior english is for all.”

“I think students should be allowed to go with what interests them – as long as they understand the possible implications 4 ATAR”

“NO! [to only offering Advanced]…particularly for gender focused classes, does the fact 45 marks are the same Area Of Study matter?”

“Imagine a male, studying Chem, bio, physics, a couple of Maths subjects, Standard English is perfect…”

“What about the kids doing 2 VET, ITP, PE, Industrial tech, do they need standard English?”

“Eng so much more than writing essays 4 exams. Lets push boundaries so studs fall in love with English”

“I know pressure of getting good results! Would like to think we can make results gr8 via love of learning. Combine both 4 synergy”

How do you decide what HSC Engish courses to run and who gets to do them??

Macquarie Poem Project

GOOD NEWS STORY:

GOOD NEWS STORY:

After working with The Red Room Company last year, Macquarie Fields High School is again working with poet Lachlan Brown. This time the project goes outside the Toilet Doors and into the Sydney Conservatorium, as students dabble in a bit of history and consider their namesake through the poetic lens.

The students are writing a poem in response to Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s First Speech in the Colony. This will be read at the unveiling of a new statue of Macquarie, which commemorates 200 years since his governing began. How exciting!

You can read more about Lachlan’s workshops with the Macquarie Fields ‘Live Poets Society’ (facilitated by @imeldajudge) at the Red Room Company blog. It is interesting to see how different students have thought about the themes in the Macquarie Poetry Project, and I think Lachlan’s workshop reflections also provide a great account of poetry pedagogy.

As a poetry teacher, the power of collaboration with working poets in these projects has been a an incredible experience. One of the most important things I learned from Lachlan was how to get more out of poetry by focussing in, taking it slow, encouraging personal interpretation and wonderment, and giving students time to write (which may sound obvious, but English lessons are so darn short!)

And the students have been awestruck by the experience of engaging in authentic discussion and receiving feedback from a real, live poet. Projects like these really do increase the sense of connectedness that students have with the curriculum, as they participate in intense thinking about words, about language work, and about the role of creativity in understanding the world around them. Students in my Year 10 class were also begging to learn more about the technical aspects of language so they could improve their poems (back to basics…I think not).

To read more about Lachlan Macquarie I recommend a brief speech given earlier this year by NSW Governor Marie Bashir. Macquarie’s endeavours to emancipate convicts and promote their employment and equal and fair treatment are a legacy I believe we should strive to uphold, and his support of education and poetry speak especially to my English-teaching soul! I can’t wait to see the poem created for the unveiling of the bicentenary statue 🙂

Recent Comments